G-AP Theory

Theory is important because it helps us to understand and describe:

- what we do

- why we do it

- what difference it is likely to make

The G-AP framework is underpinned by the following theories:

- Self-Efficacy theory (Bandura)

- Goal setting theory (Latham & Locke)

- Health action process approach (Schwarzer)

- Self-Regulation Theory (Carver & Scheier)

These theories contain the theoretical constructs described below. These constructs have informed development of each of the G-AP stages:

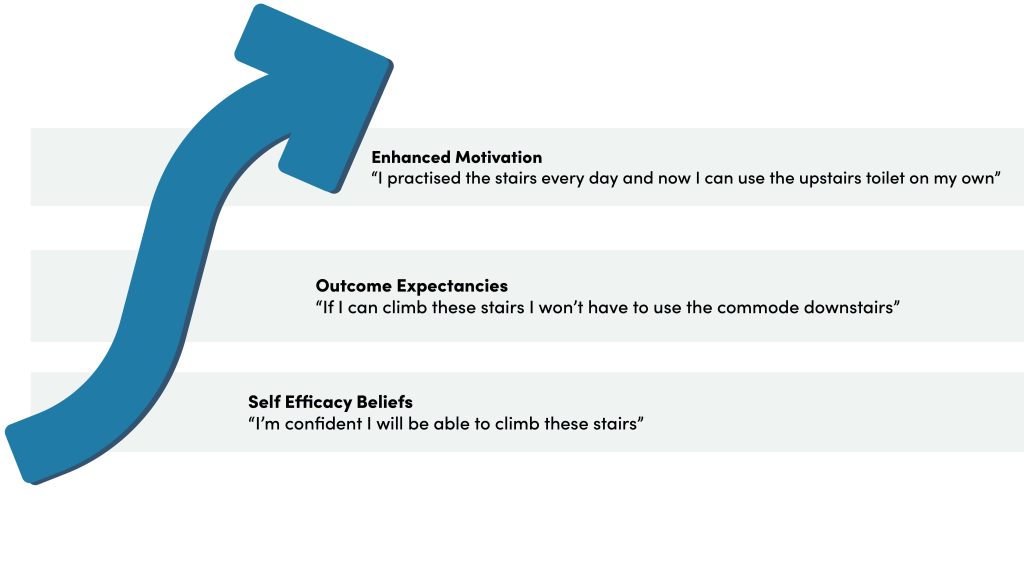

1. Self-efficacy (confidence)

“Can I achieve this goal?” “Can I complete this action plan?”

- Self-efficacy relates to how confident the person is in their ability to achieve a desired goal

- High confidence levels will motivate the pursuit of goals and plans; low levels will de-motivate pursuit of goals and plans

2. Outcome expectancies

“Will achieving this goal or completing this plan help me?”

- Outcome expectancies are the beliefs the person has about what the outcome of a particular behaviour will be

- Positive outcome expectancies are motivating e.g. “If I’m able to get up and down stairs by myself, it will put less pressure on my wife.“

- Negative outcome expectancies are de-motivating e.g. “If I do these exercises, my arm is going to feel sore and stiff.“

Confidence and outcomes expectancy beliefs operate together to influence a person’s confidence.

Self-efficacy beliefs, outcome expectancies and motivation.

3. Goal specificity / difficulty

“This is the specific goal I’m trying to achieve”

- Specific goals that challenge the person (without taking them beyond their limits) will enhance their performance e.g. “Aim to walk to the corner shop and back on your own by the end of the month.”

- Vague ‘do your best’ type goals are less likely to enhance performance e.g. “Try to walk about as much as you can.”

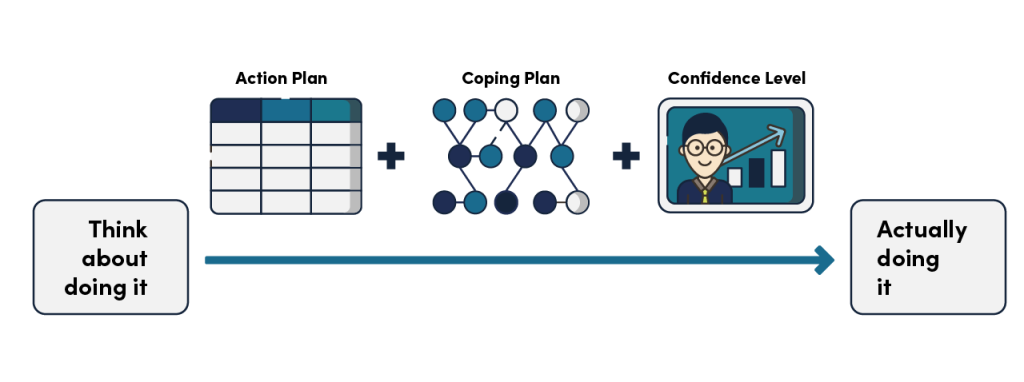

4. Action plans

“This is what I’m going to do to achieve my goal”

- Action plans get the person beyond the intention of doing something to actually doing it

- Action plans act as ‘stepping stones’ to meet specific goals

- Action plans detail exactly what the person has to do, when and how

5. Coping Plans

“This is what I plan to do if X gets in the way of me completing my action plan.”

- Barriers can get in the way of action plan completion

- Coping plans detail what the person will do to reduce or overcome the anticipated barrier

- Together, action plans and coping plans increase the chances of the person successfully completing the plan

- Feeling confident you can complete the plan is important

Action plans, coping plans and confidence: from intention to action

6. Appraisal

“How am I getting on?”

- Appraisal helps the person and the staff member to assess the outcome of the action plan and gauge progress in relation to the goal

- Appraisal takes place after the completion of every action plan; it creates the opportunity assess progress incrementally

Jane: “We went out on Saturday [with the pram]. It felt great. I just thought…this is normal. This is me

walking down the road with my wee [small] grandson. I felt fabulous. I didn’t think I was going to fall. It was just lovely the three of us out together – it was great!”

(Ref: Scobbie et al 2020)

In this example, Jane appraised how she got on taking her grandchild out for a walk in the pram:

In this example, a person reflects on how they got on with their driving assessment:

Person 7: “After I had my driving assessment, I knew the information [e.g. signs; oncoming vehicles] just wasn’t coming quickly enough. I thought it was do-able, but I’ve been realising since I got through the assessment, and how I done, that I said – this is not going to be doable.”

(Ref: Scobbie et al 2013)

7. Feedback

“This is what the person helping me with my goals had to say”

Feedback is what the staff member says to the person following appraisal of their performance.

Person 2: “Every move I made, she said well done, and indeed things cheer you up, it’s amazing what it does psychologically just to say well done!”

(Ref: Scobbie et al 2013)

If progress is good, positive feedback will boost the person’s confidence and motivate them to keep going. See the example of a person reflecting on how she felt when the staff member gave her positive feedback…

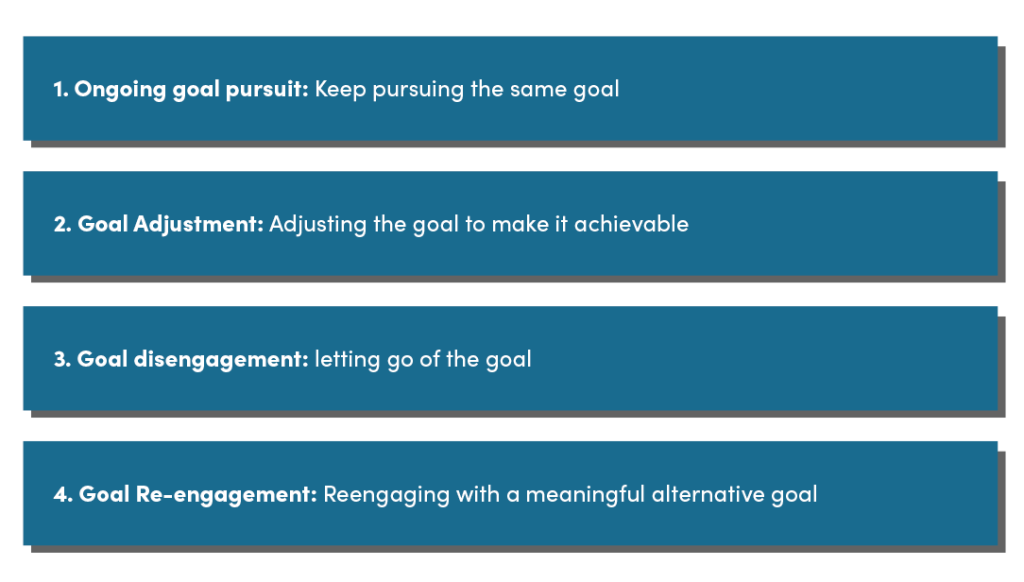

If progress is lacking, supportive feedback will support the person to think about whether they should continue with goal pursuit, consider adjusting their goal, or refocus on a different goal.

Staff member – “I think you have to be careful about how you deal with that [failing to achieve goals] with the person and how you approach it, that you do it in a positive way, saying ‘well OK, this is what we started, this is what we thought, you know, it’s not quite worked out like that, but we’ll go back and we’ll try something else’”

(Ref: Scobbie et al 2013)

Monitoring progress and informed decision making

Collaborative appraisal and feedback supports ongoing monitoring of progress and making informed decisions about what should happen next. There are four available decision making options. Each option creates the opportunity for the person to continue to make progress, even in the face of a setback.

Useful References

1.Scobbie, L. Wyke, S., Dixon, D. Identifying and applying psychological theory to setting and achieving rehabilitation goals. Clinical Rehabilitation 2009; 23:231-333, DOI 10.1177/0269215509102981.

Access via: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19293291/

2.

Scobbie, L., Wyke, S., Dixon, D. Goal setting and action planning in clinical rehabilitation: Development of a theoretically informed practice framework. Clinical Rehabilitation 2011; 25(5) 468–482. DOI10.1177/0269215510389198

Access via: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0269215510389198

3.

Sniehotta FF, Scholz U, Schwarzer R. Action Plans and Coping Plans for Physical Exercise: A Longitudinal Intervention Study in Cardiac Rehabilitation. British Journal of Health Psychology 2006; 11:23-37.

Access via: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16480553/

4.

Locke EA, Latham GP. Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: a 35-year odyssey. Am Psychol 2002; 57: 705–17.

Access via: https://www-2.rotman.utoronto.ca/facbios/file/09%20-%20Locke%20&%20Latham%202002%20AP.pdf

5.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy – the exercise of control. WH Freeman and Company; New York, 1997

6.

Scobbie, L., McLean, D., Dixon, D. et al. Implementing a framework for goal setting in community based stroke rehabilitation: a process evaluation. BMC Health Serv Res 13, 190 (2013).

Access via: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-190

7.

L. Scobbie, M. C. Brady, E. A. S. Duncan & S. Wyke (2020) Goal attainment, adjustment and disengagement in the first year after stroke: A qualitative study, Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, DOI: 10.1080/09602011.2020.1724803

Access via: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09602011.2020.1724803